Interactive Workshop on Alternative Reimbursement Models

Summary of Meeting – 09 June 2021

Facilitated by:

-

- Dr Tienie Stander

- Victoria Barr

- Kumen Chetty

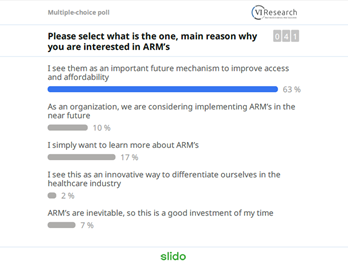

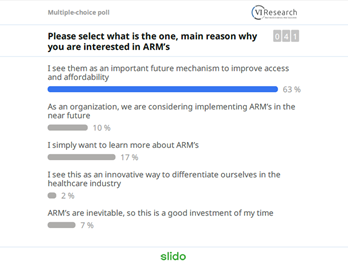

An initial poll indicated that over 60% of participants had joined the workshop because they see Alternative Reimbursement Models (ARMs) as an important future mechanism to improve access and affordability.

1. ARM’s in context

Dr Tienie Stander opened the workshop by setting out the context for the discussion: quality, access and cost form healthcare’s ‘Iron Triangle’ where difficult choices have to be made in light of limited healthcare budgets. Constrained budgets require priority setting and robust scientific decision-making about where resources should be spent. In this context, Health Technology Assessments for pharmaceuticals and medical devices have a key role to play in minimising opportunity cost.

2. Introduction to ARMs

Victoria Barr introduced some key concepts in ARMs, including that of value-based healthcare. (58% of participants said they were already very familiar or quite familiar with this concept.)

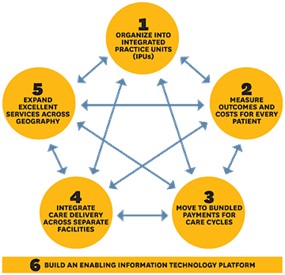

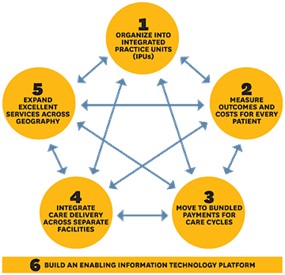

Value in healthcare is defined as patient outcomes delivered for money spent. Value-based healthcare is therefore healthcare which seeks to maximise patient outcomes and/or minimise the cost of delivering those outcomes. This agenda has been driven globally by Michael Porter of Harvard Business School, who presented a six-pronged approach in his 2013 article ‘The strategy that will fix healthcare’.

In this context, it is important to be clear on the difference between quality and outcomes; these terms are often used interchangeably but describe significantly different concepts. An outcome is something which people care about in and of itself, while clinical quality of care is only important in so much as it delivers better patient outcomes. Both concepts can be considered from both a patient perspective and a clinical perspective: quality can be thought of both in terms of patient experience of care and clinical quality of care, while we have both patient-reported health outcomes (e.g. mobility, pain) and clinical health outcomes (e.g. hospital admissions).

Contracts where payment is tied to outcomes have three major advantages: they focus attention on what really matters to patients, rather than inputs or processes; they empower providers to innovate and deliver care as they think best; and they facilitate team-based working and more integrated service delivery.

ARMs take slightly different forms in the context of pharmaceutical pricing and payment for other forms of healthcare, but the concept which ties these together is value. In pharmaceuticals and devices, ARMs are largely aimed at managing uncertainty around value (the cost or performance of a drug or device is unknown) and often involve risk-sharing between funder and manufacturer. In healthcare services, ARMs are generally used to incentivise better value delivery of care (better outcomes and/or lower cost). There are in fact many situations where the ‘Iron Triangle’ does not hold true: improved outcomes AND lower cost can both be achieved because of waste in the system. Value-based payment models often cover multiple components of the patient pathway (and can include medicines) because this allows for the maximisation of value between settings or different modes of care by internalising trade-offs within a single contract.

3. ARMs for pharmaceuticals

Around one third of participants had some experience of implementing an ARM for pharmaceuticals or devices, either as a funder or manufacturer. When asked to use one word to summarise their experience, the top three most popular terms were ‘challenging’, ‘complicated’ and ‘legal nightmare’, although ‘good’ and ‘efficient’ also appeared.

The large number of different and overlapping types of ARMs, as well as the accompanying jargon, can be confusing and off-putting. It is helpful to think of ARMs for pharmaceuticals as falling into two categories, mirroring the two components of value: those which focus on health outcomes and those which focus on cost (financial or utilisation-based models).

The international literature on ARMs presents a mixed picture. Preferences for different types of agreement seem to be moving in different directions in different countries, for example, the UK and the Netherlands are moving away from health outcome-based arrangements, while the use of these models in the USA appears to be increasing. While there have been notable successes and failures, the evidence base on the effectiveness of ARMs remains surprisingly limited, possibly because of the confidential nature of many agreements. Despite this, ARMs will continue to be implemented because the issues that they are intended to address (reducing uncertainty, improving patient outcomes, increasing realised value, and improving access to medicines) remain as relevant as ever.

Victoria outlined five key principles for developing an ARM:

-

- Clearly articulate the rationale for the ARM and its objectives

- Ensure the design of the ARM is implementable and affordable

- Develop robust governance arrangements

- Clearly specify the funding arrangements

- Develop a monitoring and evaluation framework upfront

4. ARMs for other types of healthcare

A third of participants had implemented an ARM for healthcare services at least once. The stand-out word used to describe these experiences was ‘challenging’, with ‘complex’, ‘concerned’, ‘confused’ and ‘successful’ also featuring.

Current approaches to contracting in healthcare create unhelpful financial incentives which lead to higher costs and poor patient outcomes. However, in the case of chronic conditions like diabetes, innovative contracting models can incentivise earlier investment in condition management, which results in better outcomes for patients and lower costs.

There is no single perfect payment mechanism; all models have advantages and disadvantages, and even the same characteristic, for example, encouraging activity, can be desirable or undesirable, depending on the context. The key is to choose the payment model which will best achieve the objectives of care.

ARMs can be initiated by either the payer or the healthcare provider/pharmaceutical company, but the starting point should always be value for patients and how the service delivery model or treatment protocol can be changed to improve patient outcomes and reduce cost. The payment model is only important in so much as it supports and facilitates different service delivery models and encourages desired changes in behaviour; the payment model is not an end in itself.

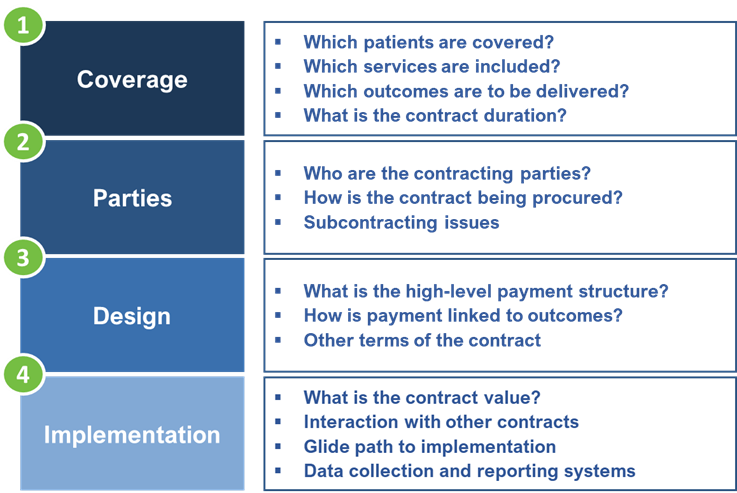

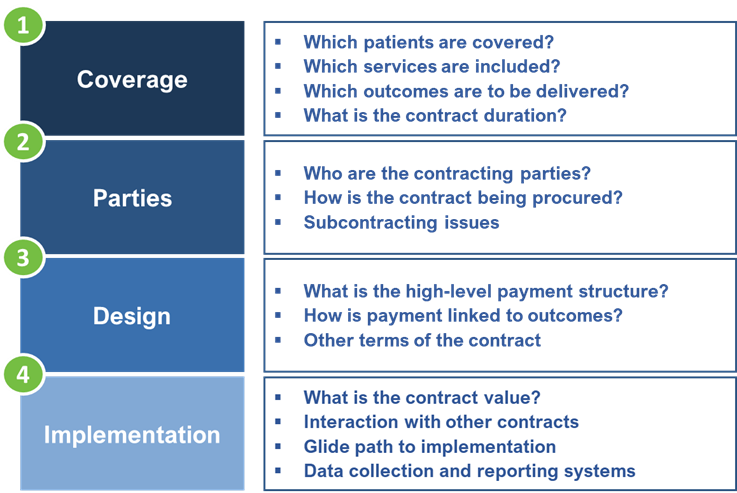

5. ARM Design Framework

Victoria presented the framework below, which she has used to develop a large number of value-based contracts both in the UK and South Africa. One of the key barriers to implementation of value-based contracts is the volume and complexity of the issues to be negotiated. The solution is therefore to work through the individual issues in a systematic and structured way, using the framework as a roadmap.

6. Case Studies

Four case studies of ARMs were presented:

-

- Developing an ARM for an oncology drug

- Multiple sclerosis risk-sharing scheme, UK

- Value-based contracts for integrated diabetes services in Liverpool and Camden, UK

- Outcomes-based capitation model for primary care, South Africa

7. Lessons Learned and Opportunities

Victoria outlined five key lessons from her experience of developing ARMs:

-

- Innovative contract development involves a large number of decisions, which together can seem overwhelming. The key is to be anchored through the process by a structured framework and to break up decisions into manageable sets.

- The process of involving stakeholders in the design of the contract is equally as important as the design itself.

- Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good: an imperfect new contract could still be considerably better than the existing contract.

- Outcomes are not straightforward to measure but they’re not impossible; some data will already exist and proxies can also be used.

- Data tends to improve rapidly once payment depends on it.

The following lessons were also reported by workshop participants:

-

- The ARM was implemented at launch but then became too complicated and funders communicated reluctance to continue so the price reduction for the asset was granted by global

- Challenge to move discussion away from affordability to value

- Culture change essential

- It’s a huge learning curve

- Payers are interested in the Rands and cents and don’t know how to deal with the complexity of setting up an ARM agreement.

- Require close continuous monitoring and collaboration between supplier and payer

- Hard work but worthwhile

- Take some risks

- Payer reluctance

- Early stakeholder engagement

80% of participants reported that they saw many opportunities for ARMs in their area of focus and the top three barriers to greater implementation were identified as:

-

- Lack of know-how/expertise with ARMs

- Regulatory barriers

- Resistance from funder

8. Q&A

The Q&A section of the workshop focused on the feasibility of implementing ARMs for pharmaceuticals in the South African context, given legal constraints and the need for approval from the Pricing Committee. There was a good discussion between representatives from the National Department of Health, the pharmaceutical industry and patient groups around how these barriers might be overcome.

For enquiries, kindly contact: kumen@valueinresearch.com

![]() Innovation and change are the driving forces behind the evolving healthcare environment in South Africa. Join VI Research as we delve into strategic solutions that harness the power of cross-functional collaboration to successfully navigate this paradigm shift.

Innovation and change are the driving forces behind the evolving healthcare environment in South Africa. Join VI Research as we delve into strategic solutions that harness the power of cross-functional collaboration to successfully navigate this paradigm shift.